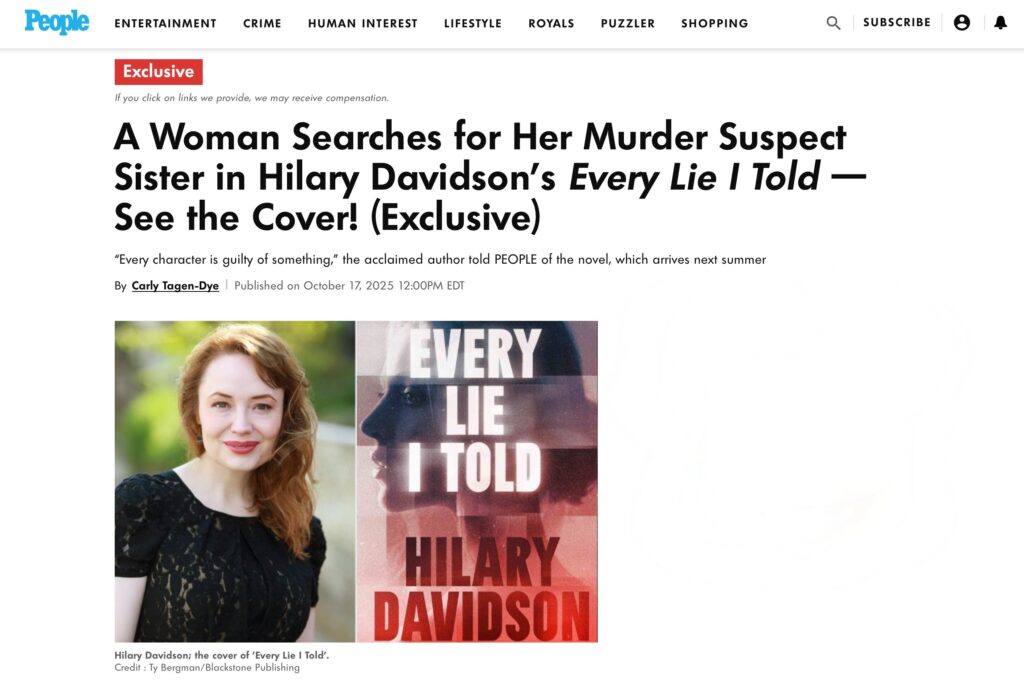

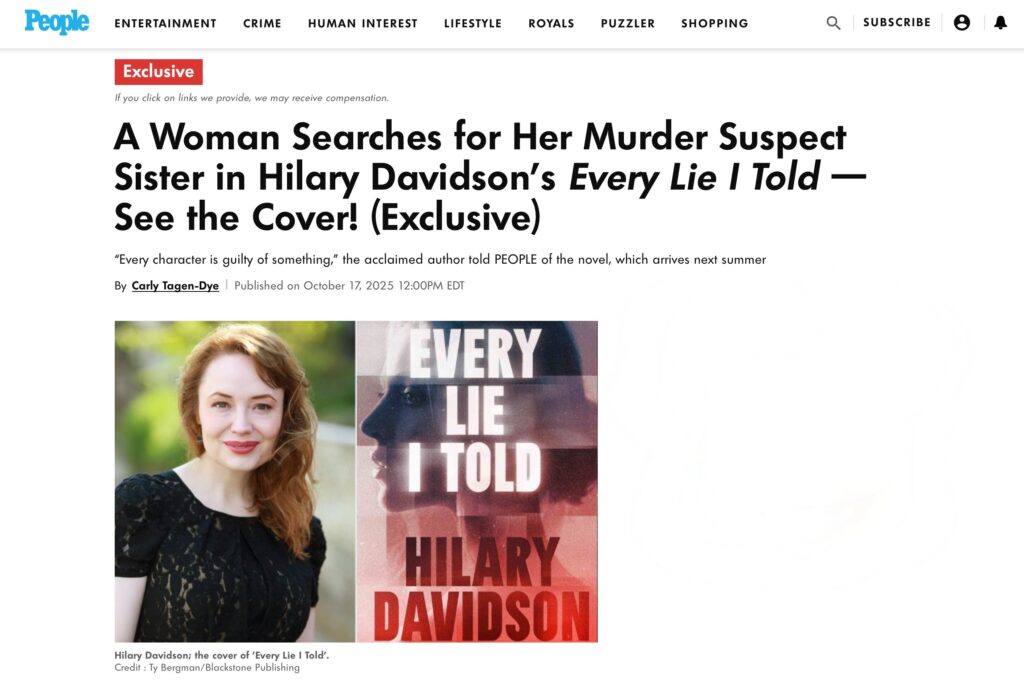

PEOPLE Magazine Cover Reveal!

To say that having the cover reveal for EVERY LIE I TOLD happen in PEOPLE is a dream come true would be an understatement. I am still pinching myself! Read the full story by Carly Tagen-Dye here.

To say that having the cover reveal for EVERY LIE I TOLD happen in PEOPLE is a dream come true would be an understatement. I am still pinching myself! Read the full story by Carly Tagen-Dye here.

I got some wonderful news today: my 2022 novella, DANGEROUS TO KNOW, is a finalist for an Award of Excellence from the Crime Writers of Canada! It’s part of the terrific series A Grifter’s Song, edited by Frank Zafiro and published by Down & Out Books. It’s a thrill and and an honor to have my work recognized like this!

I love Halloween — so what better way to celebrate than with an eBook sale? (Also with candy. Lots and lots of candy.) The three books of the Lily Moore series — The Damage Done, The Next One to Fall, and Evil in All Its Disguises — are on sale (in digital format) for $1.99 each through November 3rd. If you have yet to meet Lily Moore, now would be the perfect time to get acquainted with my globetrotting amateur sleuth. The Damage Done is set in New York City, The Next One to Fall travels through Peru, and Evil in All Its Disguises is mostly based in Acapulco. Happy Halloween!

I love Halloween — so what better way to celebrate than with an eBook sale? (Also with candy. Lots and lots of candy.) The three books of the Lily Moore series — The Damage Done, The Next One to Fall, and Evil in All Its Disguises — are on sale (in digital format) for $1.99 each through November 3rd. If you have yet to meet Lily Moore, now would be the perfect time to get acquainted with my globetrotting amateur sleuth. The Damage Done is set in New York City, The Next One to Fall travels through Peru, and Evil in All Its Disguises is mostly based in Acapulco. Happy Halloween!

Friends, you might remember that I brought my Lily Moore mystery series back into print in the fall of 2020. It was my first serious effort at self-publishing, and I had a steep learning curve. So steep, in fact, that when I decided to take direct control of eBook distribution from THE DAMAGE DONE, I had to first request to have it removed from distribution. Everything is sorted out now, I’m thrilled to say! The print edition was never affected, nor Kindle or Apple Books, but the book is now available (again) on Kobo and Nook. Here’s a short video if if want to know more.

We’ve all heard that the secret to great writing is in rewriting, but what’s the secret behind great rewriting? For an author, diving back into your own work for draft after draft is both a necessary process and a risk. How do you know if you’re actually strengthening your story, or if you’re stuck in a loop of endless revisions? What do you do if you and your editor have different visions for the book? Even though I’ve published seven novels, I still think about these issues, which is why I suggested this panel to Sisters in Crime. I’ll be moderating, and my brilliant, bestselling and award-winning panelists — authors Brianna Labuskes, Alma Katsu, and Alex Segura, and Mulholland Books editor Helen O’Hare — will discuss what goes into rewriting (and editing) to make your fiction shine. Join us — it’s free!

We’ve all heard that the secret to great writing is in rewriting, but what’s the secret behind great rewriting? For an author, diving back into your own work for draft after draft is both a necessary process and a risk. How do you know if you’re actually strengthening your story, or if you’re stuck in a loop of endless revisions? What do you do if you and your editor have different visions for the book? Even though I’ve published seven novels, I still think about these issues, which is why I suggested this panel to Sisters in Crime. I’ll be moderating, and my brilliant, bestselling and award-winning panelists — authors Brianna Labuskes, Alma Katsu, and Alex Segura, and Mulholland Books editor Helen O’Hare — will discuss what goes into rewriting (and editing) to make your fiction shine. Join us — it’s free!

Remember last August, when I told you what an honor it was to have a short story featured in Ellery Queen again? That story, “Weed Man,” is a finalist for an Award of Excellence from the Crime Writers of Canada! Yes, I am over the moon. If you’d like to read the story, you can buy the back issue from EQMM or subscribe to my newsletter (subscribers can read the story for free).

Have you heard about the Authors for Ukraine auction? It’s the brainchild of novelist Amy Patricia Meade and it features more than 250 authors and a host of terrific prizes. All proceeds benefit CARE’s Ukraine Crisis Fund (more about that below). It’s open for bidding right now! (Bidding will end on Tuesday, April 12th at 11pm EDT.) My prize pack features signed first editions of my standalone novels Her Last Breath (2021) and Blood Always Tells (2014). Please check it out — the auction is a chance to do something good in the world and get something good in return.

On a personal note, I’ve donated to Doctors Without Borders and International Rescue Committee in support of Ukraine. Until this auction came up, I wasn’t aware of the excellent work CARE is doing on the ground right now. Its Ukraine Crisis Fund strives to reach four million people with immediate aid and recovery, food, water, hygiene kits, psychosocial support, and cash assistance — prioritizing women and girls, families, and the elderly. Even if the auction doesn’t interest you, I hope you’ll check out the essential work CARE is doing.

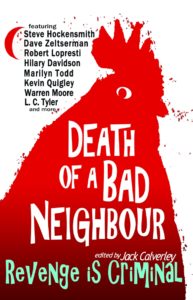

Have you ever had an awful neighbor? I have, and they seem to be a universal scourge. That’s why I immediately said yes when British author, editor, and podcaster Jack Calverley asked me to write a short story for an anthology he was putting together. That collection, Death of a Bad Neighbour: Revenge Is Criminal, is out now, with stories from Steve Hockensmith, Dave Zeltserman, Robert Lopresti, Marilyn Todd, and many other terrific writers.

My own contribution is “King of the Castle.” Here’s an excerpt:

My own contribution is “King of the Castle.” Here’s an excerpt:

The snow came down hard that early December afternoon. At first it looked enchanted, with snowflakes swirling gracefully through the air before landing on the ledge of my home-office window. As they accumulated and covered the trees in my backyard all I could think about was how postcard-perfect my view was. I was busy editing a technical manual for a client who always called me with last-minute jobs. They paid handsomely but inevitably caused headaches. In spite of the looming deadline, every few minutes I lifted my eyes from the laptop and surveyed the glorious scene. It wasn’t until my wife, Kait, came home from work that I woke up to reality.

“Fletcher, honey, there’s almost a foot of snow out there,” she said. “And you haven’t started shoveling yet.”

It was our first snowfall in our first house. Kait and I had married three years earlier, in a summer ceremony at a manor house up in the Muskoka Lakes. While we’d continued to live in my tiny studio apartment in downtown Toronto, we’d sworn to each other we’d save every penny to buy our dream home. And we had, moving into a semi-detached three-bedroom house on the far eastern edge of Danforth Village, a short walk from restaurants, shops, and the subway. We’d been there for two months, painting and re-grouting and enjoying our new space.

One of our friends had given us a sturdy red snow shovel as a housewarming gift. Welcome to the wonderful world of homeownership, he’d told me. You’re your own superintendent now.

His words were ringing in my ears as I trudged to the garage out back—we didn’t own a car, so that was our storage space—and located the shovel. Kait was right; the snow was piled at least a foot deep.

At the front of the house, I took a deep breath and told myself I needed the workout. I’d canceled my gym membership—part of our belt-tightening scheme to afford a house—and had only started setting up a workout space in the basement. At least shoveling snow promised to be a full-body workout. I pumped myself up so much that I cleared not only our side of the house but the next door neighbour’s as well. He was an elderly man named Max Bode, and we had yet to meet him, though we’d caught glimpses of his short, bony frame. We considered ourselves lucky because we had yet to detect any noise from him through the wall that our houses shared.

After I finished and returned the shovel to the garage, I noticed the light was on inside Max Bode’s kitchen. Like ours, it was at the back of the house. I figured it was as good a time as any to introduce myself, so I headed up his steps. Our neighbour was sitting at a Formica table, his back turned to me as he hunched over a newspaper. Long strips of white hair were carefully combed over an otherwise bald pate.

I tapped on the glass of the storm door.

“Go ahead, Dick, it’s open,” he said without turning around.

Vaguely I wondered if Dick was one-half of the elderly couple who’d sold their house to Kait and me. It didn’t really matter. “Hello, there. It’s Fletcher Lemire,” I said, pushing the door open. “Your new neighbour. You’re Max Bode, right?”

“In the flesh. And I don’t care much for neighbours, new or old.” He turned in his seat and glared at me with dark, protruding eyes. Up close, he was younger than I’d thought—maybe only sixty or so—but his skin had an unhealthy pallor not unlike the paste we’d used to hang our new wallpaper. “What do you want?”

“You probably noticed it’s snowing,” I said, fighting the urge to call him sir. The neighbourhood had impressed me for its friendliness, and I was caught off guard by his brusqueness. “I was shoveling our steps and the sidewalk and figured I’d do your side, too.”

“I don’t need your help.”

“It’s already done,” I said. “It’s all cleared now.”

“Bully for you. If you think I’m giving you one red cent for that, you’re out of your mind.”

“I’m not looking for you to pay me.” I was incredulous. “I’m your neighbour.”

“Then what do you want?”

I shrugged. “I guess I figured you should know that you don’t have to clear the snow.”

His lipless mouth tugged back in a tight little smile. “I don’t have to do anything. This is my house. I make the rules. If I don’t want to do something, I don’t.”

“That sounds great, until the city gives you a ticket for not clearing your walk.”

He chuckled at that. “No one’s giving me a ticket. Bye now, Dick.”

“It’s Fletcher,” I said.

His lips grinned a little more broadly, as if I’d made a joke. “Of course it is. Millennials and their stupid names.”

Want to read more? Death of a Bad Neighbor is out now in hardcover, paperback, and on Kindle. I hope you’ll check it out!

I couldn’t be more thrilled to be leading a virtual reading group at Brooklyn’s Center for Fiction! “Agatha Christie’s Heirs: Modern Mysteries Inspired by the Queen of Crime Fiction” will start on Thursday, March 10th, at 7pm EST. Here’s the course description:

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of Agatha Christie in the world of mystery fiction. Between 1920 and 1976, Christie published some 75 novels, 165 short stories, and 16 plays—a body of work that continues to fascinate and delight readers around the world. Christie’s fiction—and her perennially popular detectives Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot—endure in part because her impeccably crafted mysteries are logical puzzles that are almost unsolvable, and yet can be worked out by the most attentive readers. (Christie always provides the necessary clues, albeit in a mass of red herrings.)

Christie’s work has inspired many modern crime writers, who have created their own captivating locked-room mysteries and unforgettable detectives. The contemporary writers this course focuses on bring varied perspectives to their books, exploring themes of class, race, and gender, broadening and deepening the appeal of their work. Some are set in international settings far from Christie’s English villages, but all will intrigue fans of her classic mysteries.

I hope you’ll join me! (Since it’s virtual, you can join from anywhere.) Sign up now at www.centerforfiction.org.